Your job is to help Rama escape his own labyrinth of bereavement, self-pity and tortured creativity.

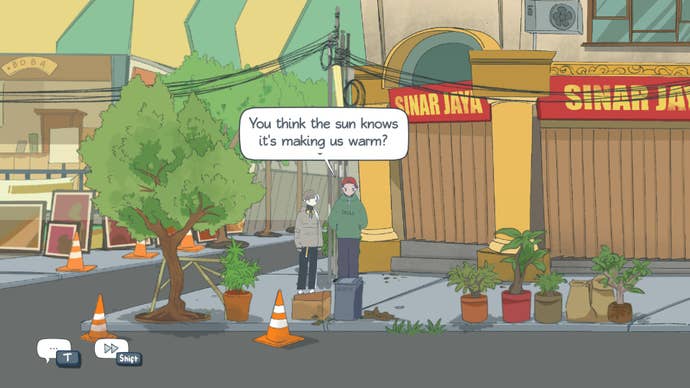

I like Afterlove EP’s deft writing, and enjoy its splendid and specific recreation of 21st century Jakarta.

But I do not much like being Rama’s friend, at this particular moment in his life.

And by extension, I did not enjoy a lot of Afterlove EP, much as I admire it.

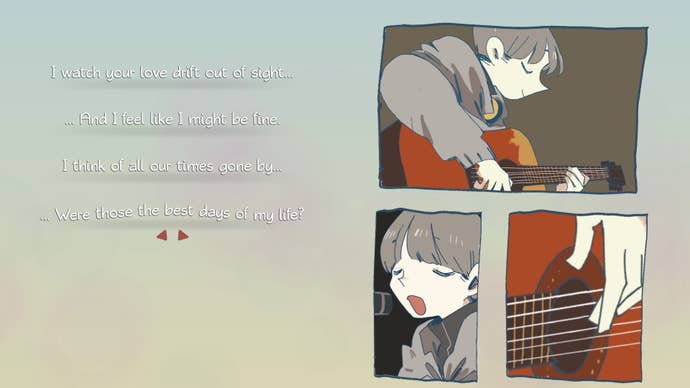

(Among his other faults, I found Rama to be an abysmal lyricist.)

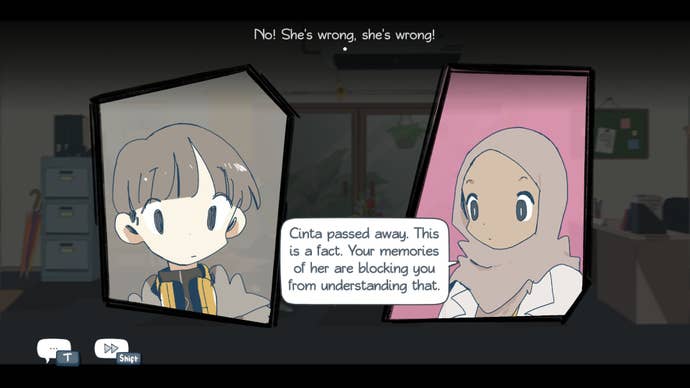

The constant throughout is the mysterious disembodied voice of “Cinta”.

Rama is the only character who can hear her.

Cinta is that idea thrown into a crockpot withphantom Chef Gusteau from Ratatouille.

Thankfully, Afterlove EP is very much concerned to dismantle this soggy masculine hallucination.

She is by turns the angel and the devil on his shoulder.

At her worst, she relentlessly misinterprets feedback as mean-spirited, and prompts him to lash out.

She discourages him from opening up to his therapist.

The progress from one Cinta to the other isn’t smooth or irreversible.

“You couldn’t see me outside of your own expectations,” she says, at one point.

Plus ca change, etc.

This echoes the tough love Rama receives from Tasya and Adit.

During a rehearsal of new material, Tasya expresses ambivalence about Rama’s lyrics.

The way he writes about Cinta is reductive, she says, condescending.

Cinta was so much more than this.

The Cinta in your ear is atypically withdrawn during this exchange.

Admittedly, I came and went with the game’s art direction.

“There’s something so beautiful about the simplicity of painkiller packaging,” they tell you.

“Somebody chose this color.

This is somebody’s art.”

Thankfully, that’s not how it plays out.

Gosh, that’s a fair amount of praise, given how I opened this review!

Again, the big issue I have with all this is simply that I do not like Rama.

Spending time with him makes me feel the need to shower.

At his worst he is a caricature of a sadboi slouching around his own personal hall of carnival mirrors.

Rama is the functional centre of the universe, even when the aim is to defuse his melancholy narcissism.

Any lessons in empathy involved are thwarted by this sheer availability, which characterises them as unpaid therapists.

In short, the choice of formal precedents both supports and undermines the tale.

This is much more of a problem when it comes to those Good and Bad endings.

These compress the mushy unpredictability of grieving into a rigid puzzle.

By contrast, my approach to healing Rama was to distribute attention considerately between the cast.

I get that visual novels are known, even celebrated, for such whiplash.

Finishing the game and writing this review has been an agonising, spaghettifying descent from grudging empathy into loathing.