So saysDoomdesigner John Romero on the subject of his relationship with John Carmack.

Yet any lasting acrimony has now dissipated.

The latter praised Romeros remarkable memory, and waxed wistfully about their shared impact on the gaming medium.

People just didnt know, Romero says.

It was funny when I had other people come into a Zoom call with John.

The two Johns joked around, speaking with the familiarity of old colleagues.

People dont know what it was like when we were working together.

Still, Romero acknowledges that communication often broke down inthe early days of id Software.

We were just these 20-somethings running a giant company that had done really well, he says.

It required a totally different situation, because of the other people on the team.

We didnt take that into account.

We wouldnt have had to split up.

Today, the two Johns have reunited for alivestream.

The moment, precisely three decades ago, when they releasedDoom.

By then, id Software had already put outWolfenstein 3D, and a global audience awaited its next game.

But they werent nervous about pressing the launch button on their follow-up project: We were just tired.

Much has been written about Doom in the years since.

The adrenaline rush of its action, the knotty unpredictability of its levels.

But an important part of the story has often been left out.

Romero is of both Yaqui and Cherokee ancestry.

Doom is an indigenous design.

Its not something he was conscious of back in 1993.

Basically a white family situation.

I didnt think about [my heritage].

It wasnt ever treated differently in school, it just felt like everyone else.

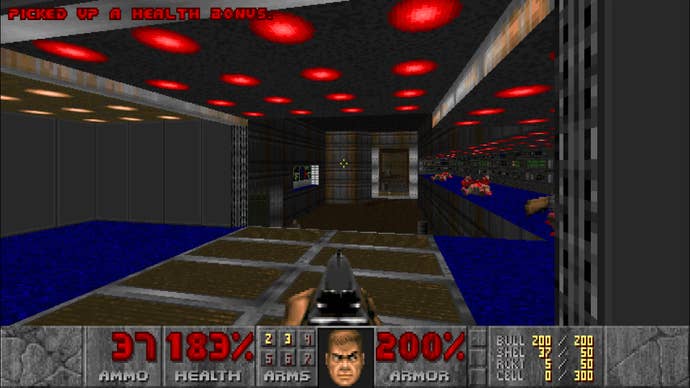

To me, the environment is the most important character in the game, he says.

I got thinking about, what do I want?

I want landmarks I can visit multiple times, Romero says.

There are ghosts forever.

Stories take place, and its just information thats valuable, and it doesnt matter when it happened.

That sense of history, still relevant in the present, is certainly recognisable in Doom.

Its a timelessness thats been reflected at a broader level, too, over Dooms three decades of existence.

Simplicity is its strongest point, Romero says.

It still feels good.

You dont see any texture shimmy or wrongly drawn pixels in the world.

The player feels like theyre in a real environment that obeys its own laws.

The movement is extremely solid, even though its really fast.

For platforming, Marios movement is basically perfect.

And I think for Doom, its basically the same thing.

Dooms engine was min-maxed according to principles that still stand up today.

It didnt matter how many things were gonna happen on screen, Romero says.

It was always gonna draw at 35 frames.

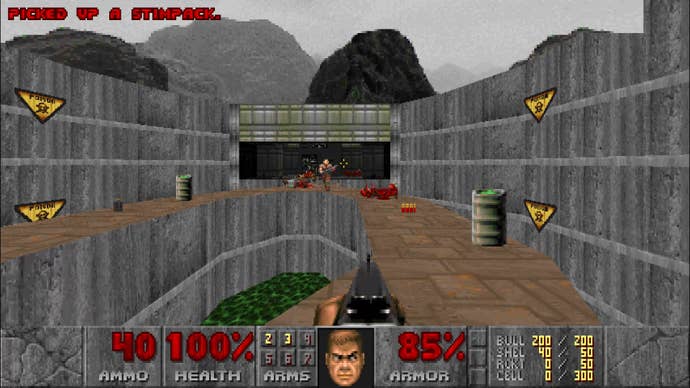

And thentheresthemodding, which has ensured that Doom is not just playable but still living and evolving.

Its kept the game going, Romero says.

Todays tools are amazing, he says.

Its funny, because I believe that Doom level design has still not been exhausted.

Im still doing new things.

Many of Sigil IIs secrets relate to a notoriousfireblutexture from the original Doom.

Its a total meme in the Doom forums.

And if you shoot it, you will launch the secret fireblu room.

So you cant get 100% on the level until you find fireblu.

This kind of playful antagonism has been a characteristic of Romeros level design since the 90s.

Oh hell yeah, its amazing, he says.

People are lucky to have anything like that in their career.

If you want to remember and talk about Doom, that is 100% great.

Ive gotten more serious about it since the early 2000s, he says.

Because I would see things printed, not just about myself but other people’s stuff, thats wrong.

Correcting them is important, he says.

Because people will use that information for books and for their theses.